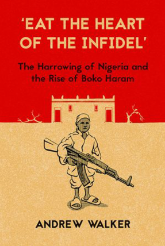

My Review of Andrew Walker's ‘Eat the Heart of the Infidel, published in 2016

I read it between 9th August and Sunday 13th August, 2020. Walker was a journalist with Daily Trust and BBC when he wrote this book in 2016. It is a well-researched book which traces the beginning of Boko Haram insurgency in the North East from the power tussle between the Hausa and Fulani communities to the contemporary time of the powerlessness of the Nigerian military to contain it. The title of the book is from the speech Abubakar Shekau made in 2014 “Shekau! Eat the heart of the infidels, since infidels want to disobey Allah.”

Walker first locates the radical Islamic ideology being championed by the Boko Haram sect in the purist agenda previously advocated by different radical Islamic scholars such as Shehu father of Othman dan Fodio who waged different wars to correct “heathen practices”, Abubakar Gumi who challenged prevailing Islamic customs, and Mohammed Yusuf, who set and enforced strict standards of religious practice and started Boko Haram on the ideology that “Western education is forbidden.”

Walker's first-hand interviews with some prisoners, political and religious leaders and even some Boko Haram members add considerable weights and authenticity to the book. From the book, three categories of Boko Haram members are identified: Ideologues, those who join by coercion or fate, and those who join for money or have scores to settle with others. It will not be difficult for readers to agree with the second category because of the different speculations about the wealth of Boko Haram in hard currencies.

Walker also details the activities of colonial officers in the region such as Hans Vischer, Heinrich Barth, Frederick Lugard. Vischer started the education policy in the region, while the name Chibok was derived through one of the circumstances in one of Barth's travels. However, Lugard sharp practices stand out in the novel particularly his classic statement that “My maxim is do not go to war and shoot down natives if it can possibly be avoided, but if you do start, give them a lesson they will never forget.”

Walker also sheds lights on the rot in Nigerian education, security and political systems. He identifies the 'certificate culture' as the rot in the education system Yobe-for-complaint as one of the main malpractices in Nigerian police and stomach infrastructure as the bane of Nigerian politics. These rots are indisputably most abiding devils which Nigeria is yet to dispense with.

When I decided to read it, my thought was that the book would have unusual harrowing tales to tell about the numerous havoc Boko Haram has wreaked in Nigeria, particularly the North East. But it was first wearing me out because Walker starts it from the very beginning of Islamic revolutions in the region. Nevertheless, I decided to read it to the end and I began to feel vicarious thrill when I read about past military administrations, particularly Muhammad Buhari's regime and his WAI and Umaru Dikko's saga. In all, the book outlines how the Nigerian security forces have been outstretched beyond breaking points in the course of their efforts to curtail Boko Haram insurgency.

Comments

Post a Comment